Peanut butter spans time, cultures, and countries. Whether it’s served in a dipping sauce for satay, used as a base for African soups or spread onto bread with jelly (or bananas, or honey, or bacon) we can’t get enough. The average American eats around 3lbs of peanut butter every year. It’s a delicious spread that is as versatile as it is nutritious. But exactly who invented peanut butter? Let’s find out the real story behind our favorite treat.

Peanut butter isn’t a new phenomenon. It’s said that the Incas consumed their form of the spread in the 1400s. Around the same time, Africans started pulverizing peanuts to use in their stews. By the time we reached the Civil War, soldiers got much of their caloric needs from a porridge made from peanuts. But these are far cries from the peanut butter we eat today.

Modern peanut butter is pretty new. It traces back to less than 150 years ago, or the late 1800s and early 1900s. It was the ingenuity and foresight of four men that took that simple legume and turned it into jelly’s favorite sandwich partner.

And it all started with a missed opportunity.

The Peanut Butter Pioneers

George A. Bayle Jr.

In the late 1800s, the owner of a food product company, George A. Bayle Jr. took a meeting with an unknown doctor. The physician had a suggestion for the merchant.: produce and distribute a peanut paste for patients who could not chew. This was a common issue in the 1800s. Many people needed a source of protein that didn’t require teeth or jaw strength to consume. Bayle Jr. saw the public need and business potential. He developed a process to make a peanut paste and started selling the product in bulk for $0.06/lb.. It was a hit.

It was around this time that the US approved its first patent application for peanut paste…to someone else.

Marcellus Gilmore Edson

In 1884, a Canadian chemist named Marcellus Gilmore Edson issued a United States Patent for “Peanut Paste”. His application described the paste as having a “consistency like that of butter, lard, or ointment”. Edson’s inspiration for the product was the same as Bayle Jr.’s. To provide a healthy source of protein for people who could not chew. But Edson’s peanut paste wasn’t like Bayle Jr’s.

Edson’s secret was that he roasted the nuts before milling them until they reached a “fluid or semi-fluid state”. Afterward, he added sugar to the paste to harden the consistency and boost its flavor.

While Edson owned the patent for the paste, he hadn’t secured a patent for the process to make the paste. That went to a certain well-known cereal man just one year later.

Dr. John Harvey Kellogg

Dr. John Harvey Kellog – yes that Kellogg – also started toying around with peanut butter as a protein source. As a vegetarian and a doctor, he understood the need for meat and chew-free nutrition. This kind of problem-solving was not uncommon for the doctor. Kellogg and his brother, W.K. Kellogg, ran a sanitarium called The Western Health Reform Institute in Battle Creek, Michigan. It was here that the brothers started inventing recipes to meet the needs of their patients. This is how and why they gifted us all with Corn Flakes.

Dr, Kellogg’s peanut experimentation was successful. In 1885 he patented the “Process of Preparing Nut Meal”. The patent details “a pasty adhesive substance that is for the convenience of distinction termed nut butter”. The product was different than it is now. They used steamed peanuts instead of roasted, and the outcome was similar to Edson’s. Eventually, W.K. left the sanitarium to open the Sanitas Nut Company. The business’s purpose was to distribute their new peanut butter to retailers.

Before they found success with cereal, the Kellogg brothers were all in on peanut butter.

Peanut Butter’s Push Towards Popularity

Ambrose Straub

Twenty years after the US recognized Edson’s peanut paste, Ambrose Straub patented a revolutionary peanut butter machine. In previous production methods, they would ground crushed nuts, often by hand. It was inefficient and difficult and resulted in inconsistent textures. Straub’s new machine not only made the process a lot easier to streamline, but it paved the way for further innovation from other creators.

C.H. Sumner

In 1904, a man named C.H. Sumner used one of Ambrose Straub’s machines to make peanut butter for the World’s Fair in St. Louis. He was the only person selling peanut butter at the event, and it was a sensation among the guests. He sold $705.11 worth of the product. That equals roughly $20,360 today! Thanks to Sumner, people from all over tried peanut butter for the first time. An act that created a buzz among consumers outside regional or medical niches. The success at the World’s Fair showed food companies that this was a product worth commercializing.

Joseph Rosefield

Almost three decades after Edson and Kellogg filed their patents, a man named Joseph Rosefield took a huge step toward mass-producing peanut butter. He made it shelf-stable. Up until this point, manufacturers made and sold peanut butter only in their regions. The fat in the peanut butter made it unstable for travel. Its natural oils would rise to the top of the spread which made it susceptible to oxygen exposure. That would cause the oil to go rancid, and the product to spoil. If peanut butter was going to meet the potential demand from buyers, it needed the keep its shape, so to speak, to make deliveries possible.

Rosefield saw a great business opportunity and he took it. He created a method that wasn’t unlike churning actual butter. He used hydrogenated peanut oil to emulsify his peanut butter so that it would not separate in storage. The resulting product was very smooth, less prone to spoilage, and could last on the shelf for up to a year. It was a game-changer for the future of food preservation, and the patent for this shelf-stable peanut butter was all his.

Rosefield chose to license the patent to Swift and Company, better known as Peter Pan. In 1932, they parted ways so that he could start his own peanut butter company. He named it Skippy.

George Washington Carver

Geroge Washington Carver is synonymous with peanut butter. The truth is, he had nothing to do with its invention. He did, however, conduct a lot of research around the peanut so the claim isn’t offbase.

Carver was an agricultural chemist whose work helped local farmers capitalize on their goods beyond eating or drinking. In 1903, he started researching alternative uses for peanuts at the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama. Carver developed over 300 uses for the legume and he refined peanut horticulture by promoting its use in non-food items like shampoo and printer ink.

He may not have invented peanut butter, but he does have quite the legacy. Beyond his reputation as the “father of the peanut industry”, he was a brilliant botanist at a time when African Americans faced violent public oppression. He managed to command respect in his field mere decades after the US ratified the 13th amendment.

His motivation was a more sustainable planet so you could say that he was ahead of his time. Carver sought solutions for regular problems by using plant products like peanuts, pecans, soybeans, sweet potatoes, etc., and he forever changed the way we make countless everyday items like bleach, shaving cream, mayonnaise, paper, and even wood stain.

True to his mission, he wasn’t interested in profiting off of his discoveries so he rarely applied for patents. As it reads on this gravesite “He could have added fortune to fame, but caring for neither, he found happiness and honor in being helpful to the world.”

Modern Peanut Butter Patents and Failures

The Peanut Butter and Jelly Sandwich Patent

There are a few standards by which examiners judge patent applications. For instance, you cannot patent something that is already known among the public. The purpose of patents is to support and encourage innovation. If there’s no opportunity for newness, there’s no need for a patent. J.M. Smucker Co. learned this the hard way when they tried to patent peanut butter and jelly sandwiches.

In December 1999, Smuckers successfully patented a “sealed crustless sandwich.” Aka Uncrustables. These frozen, crustless, and sealed PB&Js forced the world of patent law to once again question what should and could have the right to exclusivity. When Smuckers started to hand out cease-and-desist letters for products resembling Uncrustables, one company fought back. They challenged the validity of the patent, but Smuckers maintained that their sealing process was unique. According to them, it was new and thus worth the patent. A federal appeals court disagreed. They noted that sandwiches are not “novel or non-obvious enough” to claim as intellectual property. They revoked the patent.

Smuckers still makes and sells Uncrustables. But so do many other competitive companies – under different names, of course.

Plumpy’Nut: With Great Power Comes Great Responsibility

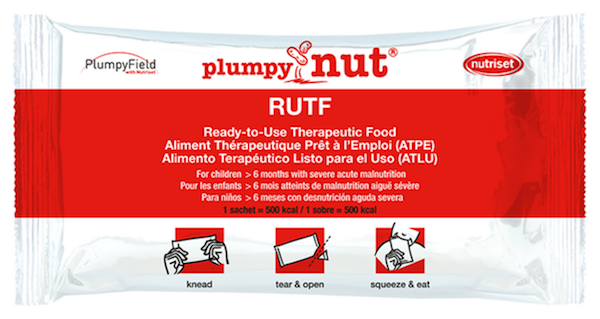

Plumpy’Nut is a product made from peanut paste. The intent behind Plumpy’Nut is to treat severe malnutrition during emergencies and in impoverished nations. It is easy to eat, requires no preparation, and lasts up to two years. Containing protein, fat, vitamins and micronutrients, it helps underfed individuals gain weight.

The French company, Nutriset, currently owns the patent for Plumpy’Nut. The patent includes any pastes made from nuts for nutritional treatments. It’s considered all-encompassing, and to some, rigid, leaving little room for others to build off of. This might be a petty complaint if it weren’t for the seriousness of the subject. Plumpy’Nut saves lives, but it’s difficult to produce as dictated by Nutriset’s patent. Many agree that humanitarian responsibilities must come into play if a patent protects something that solves a crisis.

Nutriset’s stance on forceful patent enforcement prevents anyone else from making similar products – even if the intent is to serve starving populations. Their one exception is in countries where they do not own a patent. For instance, they allow select African-based non-profits to make Plumpy’Nut without paying the licensing fee. But many critics agree that this is not good enough.

At least two US-based non-profits have attempted to sue Nutriset. They fought for the right to make and distribute the paste without paying a fee. They contended that children were dying because the company was too protective of their patent. They were not successful in their suit. Still, some suggest that Nutriset’s assertiveness remains stubborn, monopolizing, and even abusive.

The Peanut Butter Pump

In 2017, a single dad named Andy Scherer invented the Peanut Butter Pump. When his 3 boys were growing up, they loved taking PB&Js to school for lunch. Scherer says he spent his sandwich-making time thinking about how much faster he could whip up lunch if he had a peanut butter pump.

It wasn’t until his kids were almost out of school that he found the chance to toy with his idea. His company laid him off and he decided to use the opportunity to try his hand at inventing.

The patent for the Scherer’s Peanut Butter Pump is still pending, but it has nonetheless gained notoriety from media outlets and a memorable appearance on Shark Tank. The investors rejected his idea, but the pump exceeded its crowdfunding goal and is currently available for pre-order.

Peanut Butter’s Journey From There to Here

Peanut butter has gone on an impressive journey – from the Incas to that unknown St. Louis physician to the Peanut Butter Pump. And despite a rise in peanut allergies and contamination outbreaks, peanuts and peanut butter are still among the most popular consumables in the United States. Not only do we love peanuts more than ever, but we’re also still inventing new ways to enjoy it. You can now buy products like peanut butter powder and peanut milk while items like peanut butter slices seem to always be in development.

However you enjoy it, you can thank Marcellus Gilmore Edson, Dr. John Harvey Kellogg, Ambrose Straub, and Joseph Rosefield. With their resolve, they paved (or is it spread?) the way for one of America’s all-time favorite treats.

Are you ready to become an inventor?

Getting your idea out of your head and into your hands is only the first in a long set of steps towards becoming a successful inventor.

First Steps To A Successful Invention

At Invention Therapy, we believe that the power of the internet makes it easier than you think to turn your invention idea into a reality. In most cases, you can build a prototype and start manufacturing a product on your own. Changing your way of thinking can be difficult. Being an inventor requires you to balance your passion with the reality of having to sell your products for a profit. After all, if we can't make a profit, we won't be able to keep the lights on and continue to invent more amazing things!Please subscribe to our Youtube Channel!