Only one name appears on both the Hollywood Walk of Fame and the National Inventors Hall of Fame. That name is Hedy Lamarr, actress and inventor. With sharp intelligence and breathtaking beauty, her story is nothing less than astonishing.

Hedwig Eva Maria Kiesler was born in 1914 in Vienna, Austria-Hungary. Her father was a banker, and her mother was an accomplished pianist. The performing arts were part of her life. She was captivated by music and acting, and she knew even as a child that she wanted to be an entertainer. Her scientific curiosity and intelligence became apparent at a young age, as well. Her father fondly remembered her attempting to disassemble and reassemble a mechanical music box at five years old.

Her early career

It’s hard to overstate how compelling people found her. Lamarr won her first beauty contest at age 12. At 16, Lamarr was taking acting classes, working as an assistant on movie sets, and appearing as an extra in film productions. After her first small speaking role in 1931, she was discovered by Austrian/German producer Max Reinhardt. He brought her to Berlin, where she was introduced to Russian director Alexis Granowsky. He cast her in a supporting role in his film debut, the 1931 Trunks of Mister O.F.

Her star rose rapidly, and the next year, she was given a role as a leading lady in Carl Boese’s Man Braucht kein Geld (No Money Needed). In 1933, she became famous as the lead of the film Ecstasy by Gustav Machaty. Lamarr’s beauty—and highly sexualized and controversial performance—won the film’s lead role, which gained her international fame. This film was banned in Germany and the United States due to its risqué content, although it was celebrated as art in much of Europe.

Her acting interrupted

Her on-screen performances were under her maiden name, Hedy Kiesler, until her marriage to Friedrich Mandl, an affluent arms-dealer. She was only 18 and accepted his proposal over the objections of her parents. The marriage almost destroyed her career. Despite meeting her through her work on stage, Mandl forbade her from acting and kept her away from friends and family. Lamarr would later write that he made her feel like an object and treated her like a prisoner in their house.

Mandl had close ties to the increasingly fascist Italian government and the Nazi party. At his meetings with scientists and researchers, Lamarr was treated more like a “beautiful doll” than a person. She used this to her advantage and was able to observe and learn quietly. She was horrified to learn of experimental weapons, and the prospect of Europe ripped apart by another war.

Her career reignited

Marriage to the unkind and controlling Mandl eventually became intolerable, and Lamarr disguised herself after a dinner party in order to escape to France. She later moved to England. In 1937, living in London, she was introduced to Louis Mayer, co-founder of the American film studio MGM. He recognized her beauty and charisma and persuaded her to come to America, where he began to promote her as the most stunning woman in the world.

Her first starring English-language role was in the 1938 movie Algiers. The film was a success, and it was clear that audiences were fascinated by her immediately. Her next starring role was in the 1939 Lady of the Tropics, in which Lamarr played a half-Vietnamese femme fatale. Her first big, profitable hit was in the Oscar-nominated Boom Town in 1940, also starring Clark Gable and Spender Tracy. She first received top billing in 1941 for “H. M. Pulham, Esq” (it was uncommon at the time for even popular actresses to be named before a male co-star).

She starred in dozens of films and a number of the biggest hits of the day. Lamarr was often compared to Greta Garbo and Marlene Dietrich, and quickly became known as a Hollywood go-to for “exotic” and seductive roles. This typecasting made her increasingly frustrated. Despite her remarkable acting skill, she would often be given substantial screen time but comparatively few lines. Her looks were so unique that Disney supposedly took inspiration from her for the design of Snow White.

A growing dissatisfaction with her roles

The intelligent Lamarr became bored with the repetitive nature of the characters she portrayed. Her last film at MGM was something of a departure from the typecasting, playing a European princess in Her Highness and the Bellboy. Nevertheless, after the end of her MGM contract, she left the studio for good.

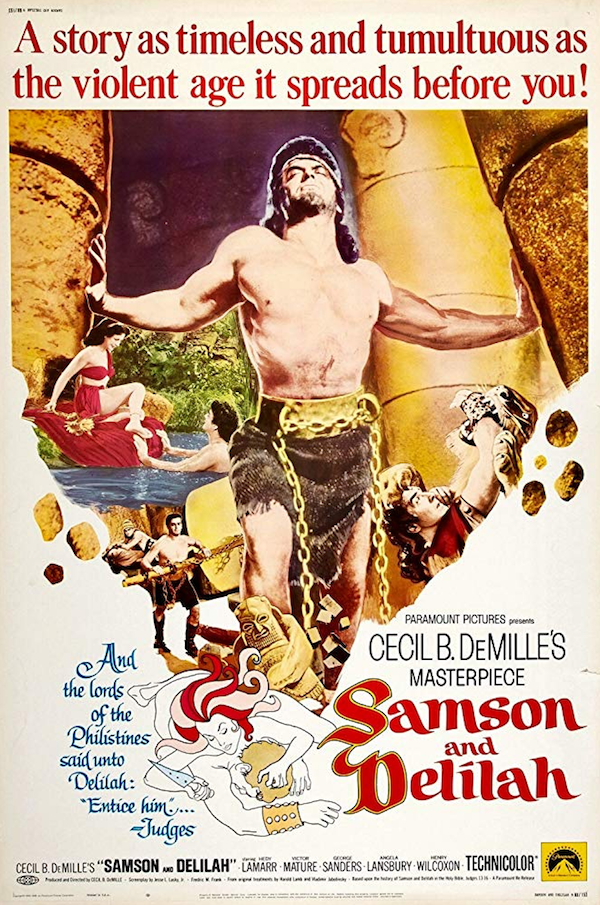

Attempts to form her own production company fizzled, and another acting success was not found until 1950 when she played one of the main title characters in Cecil B. DeMille’s Samson and Delilah. Paramount Studios film won two Academy Awards along with critical acclaim. This film is considered Lamarr’s most famous role. Reviews declared that she was perfectly cast and her sultry performance as Delilah was flawless.

She continued acting on and off with Paramount for 16 years, but Samson and Delilah was her last major success. Her last completed film was in a thriller called The Female Animal in 1958. A few false starts followed but fizzled, and her last attempt was in 1966 with Picture Mommy Dead. The role was recast after Lamarr experienced an unexplained collapse on set.

Over the course of her career, Lamarr was married five times, in addition to her first marriage to Friedrich Mandl in Germany. Most of her marriages lasted only a few years. She adopted a son in 1939 and had two biological children in 1945 and 1947.

The celebrity doctor Max Jacobson, nicknamed “Dr. Feelgood,” treated her with “vitamin shots.” It was a dangerous cocktail of substances that included steroids and amphetamines. Lamarr battled addiction for much of her life, like many stars of her time.

Political involvement and the patriotism

Although raised Catholic, both of Lamarr’s parents were of Jewish descent. In her paperwork to apply for naturalized U.S. citizenship, she marked her race as “Hebrew.” She would later refuse to acknowledge this heritage, even to her children, but she was empathetic to the plight of European Jews during World War II nevertheless. Lamarr also loathed Nazis, some of whom she had personally met during her miserable marriage to Friedrich Mandl.

Even before she became a U.S. citizen in 1953, Lamarr was highly supportive of the Allies and America’s involvement in WWII. Events she sponsored sold more than $25 million in war bonds. She also began an extensive troop letter-writing campaign at MGM. She spent time working at the famous “Hollywood Canteen,” where celebrities would volunteer to serve off-duty or newly-recruited soldiers. They did this to express the country’s gratitude for their service. They provided autographs, drinks, and dances. A popular legend states that when Lamarr was cleaning dishes at the Canteen with fellow star Marlene Dietrich, Bette Davis jokingly questioned whether “the krauts” should be allowed in the kitchen.

Return to invention

Lamarr spent much of her acting career bored and frustrated by her public persona. In an interview, she unhappily acknowledged that people tended to assume she was stupid.

Her intellectual interests and lifelong hobby of “tinkering” were rarely taken seriously until she began dating famous industrialist and aviator Howard Hughes. Hughes was one of the few people who supported her as an amateur inventor. He encouraged and taught her how to read schematics for his aircraft. Hughes called her a “genius” and offered her the tools to build a small workshop.

Hughes’ approval and Lamarr’s patriotism were keys to her significant contribution to the technologies used in modern communications.

The frequency-hopping system

During the war, Lamarr learned about a new kind of radio-guided torpedo. These were explosives carried by boats or submarines. They were launched on or below the surface of the water and exploded on contact with an enemy vessel. They were in extensive use during World Wars I and II.

Torpedoes that were aimed at heavy warships were ineffective at the time. In order to cause the most destruction, they had to be underneath a ship when exploded. During WWII, militaries began using magnets to send torpedoes underneath the keels of ships. Timers were also used to keep them from exploding until they were positioned properly. While these methods worked to some extent, there was still room for a vastly better system.

Radio guided Torpedoes that could be steered after they were launched would be an ideal technology to use, but radio waves were extremely vulnerable to interference. There was a serious danger that an enemy could easily track or jam the signal.

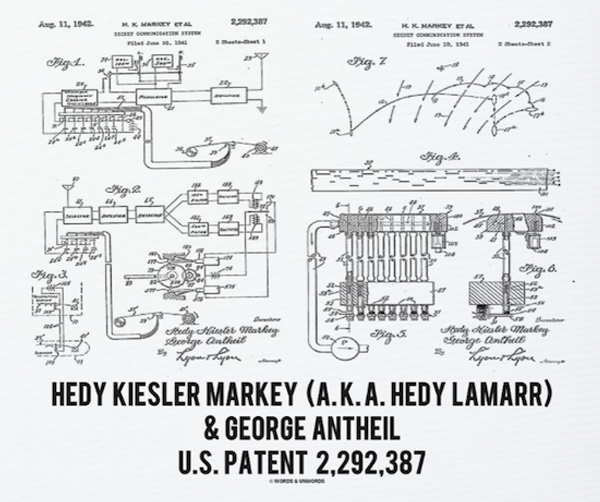

Lamarr worked with her friend, composer George Antheil, to develop a way to keep radio guidance from being so susceptible to enemy tampering. What they came up with was the “frequency-hopping spread spectrum” or FHSS.

Lamarr and Antheil received patent #US2292387 for what they called simply a “Secret Communication System,” and offered their technology to the U.S. military. Still, no effort was made to test or adopt it until the 1950s, long after the war had ended.

The science of radio waves

“Radio waves” exist on a spectrum, divided into a range of frequencies. A radio-controlled torpedo would be set to recognize only a single frequency, and that’s why it would be easy for an enemy to intercept or disrupt.

With frequency-hopping, the receiver would “hop” in a preprogrammed pattern through multiple sub-frequencies in quick succession. This method would ensure that only another device using the same pattern could control it. A radio signal could be encoded, and an enemy would have to crack the code to interfere with the weapon. Musician Antheil designed 88 carrier frequencies, based on the 88 piano keys.

Because FHSS allows a source and receiver to stay on a very narrow spectrum, two devices are unlikely to interrupt each other. Crowded airwaves are less limiting to how many communication sources can occupy them.

The U.S. Navy, perhaps in part because they simply did not take a beautiful actress and a musician seriously, did not make use of the technology until the 1960s where it was adapted for secure communications during the Cold War.

FHSS in modern times

This technology was highly influential on later telecommunications as it continued to evolve. Adaptive frequency-hopping spread spectrum was developed, with improvements in compensating for increasingly crowded airwaves. This is the science used in GPS, Cell phone, Bluetooth, WIFI, and many other types of wireless signals.

Dynamic frequency hopping, using parallel signals, allows transmissions over longer distances and reduces the signal crowding problem even further. Lamarr has sometimes been called “the grandmother of Wi-Fi.”

Acknowledgment and appreciation

Lamarr went unrecognized as an inventor for decades, but the scientific community eventually realized how much she had contributed to modern communication technology. She was the first woman to receive a “Spirit of Achievement” Award from the Invention Convention in 1997. The same year she also won the “Pioneer Award” from the Electronic Frontier Foundation. She was posthumously inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame in 2014.

The U.S. military has acknowledged her contributions as well, although neither Lamarr nor Antheil ever saw any profit from their ideas.

A complicated life

If she had been born a generation later, Lamarr might have been able to pursue science as her primary interest. Society would have allowed her to express her patriotism through technological innovation and not just as a pretty face promoting war bonds. If she had been taken seriously, her frequency-hopping system could have found military use much sooner. The naval victory during WWII might have come more easily. The world will never know what she might have accomplished with training and education in science instead of acting.

Even though she was often dismissed as an empty-headed beauty, Hedy Lamarr’s creativity and intelligence were as stunning as her performances.

Are you ready to become an inventor?

Getting your idea out of your head and into your hands is only the first in a long set of steps towards becoming a successful inventor.

First Steps To A Successful Invention

At Invention Therapy, we believe that the power of the internet makes it easier than you think to turn your invention idea into a reality. In most cases, you can build a prototype and start manufacturing a product on your own. Changing your way of thinking can be difficult. Being an inventor requires you to balance your passion with the reality of having to sell your products for a profit. After all, if we can't make a profit, we won't be able to keep the lights on and continue to invent more amazing things!Please subscribe to our Youtube Channel!